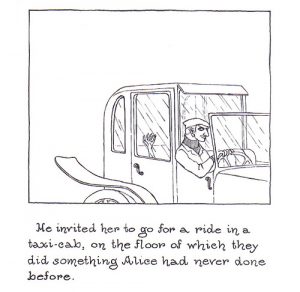

In recent weeks, we have discussed the mature and dark themes that appear in many children’s books. From Amphigorey to The Arrival, we see stories that are stylistically similar to the children’s books that we all know and love, but in fact, have a dark thematic undertone. I have always found adult themes hidden in media designed specifically for children to be interesting. For example, SpongeBob Squarepants is loaded with innuendo and adult jokes. In fact, many cartoons have such components – perhaps to entertain adults who may be watching along with their children. I’m not afraid to admit that I still watch (and enjoy) watching SpongeBob, but I must say that my enjoyment has shifted focus a bit. A lot of jokes that I find myself laughing at now, I do not think I would have understood as a child. This is why I feel that it is sometimes appropriate to integrate some dark humor and subtle adult content into media designed for children (and when I say ‘some’ I certainly mean less than in Amphigorey). Below is an example of humor that a child might not understand, but is funny to an adult. It’s not obscene (although such examples do exist in SpongeBob) but is an example of mature humor nonetheless:

Certainly, as we have discussed in class, this phenomenon is not isolated to television and extends to many children’s books as well. Looking back on some childhood favorites, it is evident that dark themes are abundant. For example, Where the Wild Things Are could be very frightening to a child. After all, playing with monsters on an island isn’t every child’s idea of a good time. An example that hits closer to home is Harry Potter and The Sorcerer’s Stone. While this novel is not your typical children’s picture book – many elementary school students read this book. I remember being absolutely terrified by this book the first time I read it. I was nervous to talk about the popular story with my friends in school because the thought of three-headed dogs, trolls, and men with two faces kept me up at night. It took me years to get back on the Harry Potter bandwagon. Another interesting example is The Lorax. It is a fun picture book and a classic, but the underlying theme about destruction and the takeover of industries is a bit dark. Nevertheless, it allows parents and children to begin a discourse about such topics early in life. Indeed, the content of The Arrival is similar in this way. The themes themselves are mature, but disguising these themes in a more playful setting introduces children to important historical events from an early age. Thus, I feel as though these themes are actually very important and can be both entertaining and educational.

When I returned from class today, I cracked open The Arrival to get an idea of how we would be ending the semester. I had high hopes for a work free of any dark themes. Admittedly, I only skimmed a few pages, but I have a feeling I will be left with the same sentiment. Looking back on the semester thus far I think that the most cheerful work that we investigated was The Secret of Kells. Considering how this movie involves the entire town being ransacked and burned, one could only imagine what the remainder of the semester entailed.

When I returned from class today, I cracked open The Arrival to get an idea of how we would be ending the semester. I had high hopes for a work free of any dark themes. Admittedly, I only skimmed a few pages, but I have a feeling I will be left with the same sentiment. Looking back on the semester thus far I think that the most cheerful work that we investigated was The Secret of Kells. Considering how this movie involves the entire town being ransacked and burned, one could only imagine what the remainder of the semester entailed.