Month: April 2016

Quick Thought on Gorrey Animation

*Warning, this was a post that was sitting as a draft because I forgot to click publish. Feel free to ignore this this week*

I am happy that you made us pick up a Gorrey book. It wouldn’t have been an art book I think I would have ever picked up. It looks too dark for something for me to pick up as a kid, which is a good thing it seems. But there is this simplicity and lightness to the work that I believe calls for its best medium to be in animation. The short clip you showed in class of the beginning to the PBS mystery series demonstrated how naturally comedic Gorrey’s characters are. To leave them stagnate in the print almost does these wonderfully creepy and endearing characters a disservice. To animate them is to add a bit more absurdity: in the exaggerated stiff animation and the bright off kilter sound effects and musical background.

Max Ernst

*Warning, this was a post that was sitting as a draft because I forgot to click publish. Feel free to ignore this this week*

It was actually the discussion we had on Monday in class that inspired my topic for my final paper for this class. I appreciated the discussion in which we commented on whether or not the female figure in Ernst’s Monday book has an agency of her own when her face is obscured by the shell. This to me spoke at the heart of what the surrealist movement is most about. The propagation of the stereotype of the femme-fatale and other sexualized images of the female identity were widely ingrained in surrealism. In fact, Salvador Dalí’s pieces, often promoted through a rather benign perspective of dreamscapes to audiences today, confront a deep seated fear of the female identity and her sexuality. His piece “The Great Masturbator” of 1929, depicts a monstrous glob of a female body painted with symbols the denote an inherent sexualization of the female and also a fear. Her face is drawn near the genitalia of a clothed but exposed male body (TANGENT: interesting thought, but again I would offer the idea that the headless male figure holds more agency that the bodiless figure of the woman. He stands erect and present where as the woman has her eyes closed and he head is cocked in a way that suggests she is begging or insatiably desiring the male form). By her breasts rests a lily, whose cylindrical crevice takes on the idenity of the vaginal canal. An army of ants walk along the folds of the mass from which the female protrudes, suggesting an unrelenting “itch” that needs to scratch. Yet amid these sexualized images, the perverse is not forgotten. A fly clutches the stomach region, performing fellatio on what can be construed as either an udder, a phallus, or a nose. A skeletal like man is painted in the desert background, appearing to have no understanding that this monster lives before him. This painting is rather disturbing, and so little discussed in the general teaching of surreality.

Collaging Through the Years

The collage workshop brought me back to my art classes in high school, middle school, and elementary school. The collage I created in class on Monday was not my first but was by far my most deliberate. Studying collage has given me a new outlook on what goes into making a collage, and what should ultimately come out. I think that my experiences with collages throughout the years follow an interesting trend. That is, my collages have become increasingly sophisticated. When I was in elementary school making a collage in art was a dream come true. I didn’t have to get marker all over my hands, or try to draw a good picture. Instead, I cut out scraps of paper, crinkled up pieces of tissue paper, curled up some colorful pipe cleaners and mindlessly glued these objects to a piece of paper. Of course, I never neglected to cover the entire page with glitter when I was finished.

As I graduated to middle school and high school my ideas began to manifest themselves in my collages, but my juxtaposition was nothing to write home about. In 10th grade, I created a collage of newspaper articles and pictures regarding 9/11. Our prompt for the project was to create something, in memoriam of 9/11. My collage integrated many powerful pictures and certainly accomplished the goal of the assignment. However, my placement of images on the page followed no particular pattern and was far from deliberate. Inspired by Max Ernst’s seamless collages in Une Semaine de Bonte, I took to collage once more this past Monday. For the first time in my life I created a collage with deliberate selection of the images and their placement on the page. The components of my collage combined into a single scene, and while my scene was not nearly as seamless as one made by Ernst, I attempted to tell a story with my placement of pictures. My juxtaposition was deliberate rather than haphazard, and my message was likely much more clear. This course has taught me a lot about art history, but I am also learning a great deal about myself as an artist. I once thought I could only become better at art if I practiced and practiced. While that may be the case for my execution, I think the commentary in my art can be improved upon without even picking up a pencil, or a pair of scissors. For example, as my story about my progression of collaging suggests, simply learning about Ernst allowed me to improve. Such phenomena remind me of the value of a liberal arts education. Indeed, what I learned in the classroom made my art better. In fact, much of what I learn in seemingly unrelated classes has proven to have fascinating connections.

Collage

Yesterday’s workshop was a good reminder of the amount of work it takes to make a collage. I mentioned before my amazement that Ernst made his book in three weeks, but actually attempting to make my own was a reminder of just how impressive Ernst’s work is. It was a fun experience to browse through magazines looking for images that would work well together in a collage. I became more aware of how much precision is required in cutting to get a good image that doesn’t look like it’s been pulled from multiple sources. Frequently the images in magazines have text or other things on the image that aren’t necessarily something I would want to include in my print, so I had to make choices of whether to try to cut out the object or leave it in the image and put it into my collage. I also thought about the fact that since we were using many different magazines, the sizes of images varied. In some pictures the people were the main focus of the page and in others they were in the background. Finding images that work together spatially and proportionally takes a lot of work if you’re looking to make a cohesive, consistent image. This workshop gave me even greater appreciation for Ernst’s work.

Collage Reflections

As I’ve learned from many of our workshops, the creating art is a lot more time consuming and difficult than it looks. I absolutely loved the collage workshop, largely because it is something that I used to do often when I was younger. In the past, my collages were just pasted images cut from magazines that I liked. I found it a lot more difficult to pull images from magazines and books that have to relate to the scene I am trying to depict, Dracula waking from his tomb. I found that it was hard to recreate such a specific scene with the content in a magazine. I think I am going to end up drawing or selecting and printing the more specific images (like Dracula and a tomb). I have also never made a collage with tissue paper and streamers before, but I really liked the way that it looked on the page, though it was hard to glue down. I think the prettiest collages are made by layering mediums, though this is the most time consuming. I am glad we are starting this final project early!

A new insight on Ernst

During the workshop today, I discovered something about Ernst’s collages. While creating my own collage, I realized that many of the pieces that I cut out I was giving new meaning to. For instance, I cut out a clown from a rather harmless children’s book. His face in my collage now looks like one of satirical nature. It goes to show that objects out of context have their meaning redefined. Which made me think about Ernst’s collages. For all I know, Ernst was collecting images of animals from a Charles Darwin book. Ernst then repurposed possibly harmless images to something of a satirical or horrific nature. I think it would be interesting to know where Ernst got his images from. In the collage I created today, almost all of my images were from the same text, one about nature. However, when I reorganized the images from a book of nature, I made a commentary about the destruction of nature by humans. I just found that I would be interesting to see if Ernst might have done something similar giving even more, commentary on already fascinating images.

Amphigorey

I can’t believe I had never heard of Amphigorey (or even Edward Gorey) before in my life, because I think his work is fantastic. The Object-Lesson is one I find especially mysterious, because things seem to happen randomly, completely without order or reason. Maybe there is a comment somewhere in there about our society and how we act and react crazily to things we shouldn’t (Madame O flings herself over the parapet after realizing that her cousin’s mustache is not his own). One page reads, “On the shore a bat, or possibly an umbrella, disengaged itself from the shrubbery, causing those nearby to recollect the miseries of childhood.” In class we learned that Gorey was very uncomfortable around children, which makes me wonder what his childhood was like. Although I hope he didn’t personally connect to the grim fates presented in The Gashlycrumb Tinies, something must have inspired him to view kids as vulnerable to horrible experiences.

Categorizing Edward Gorey’s Work

Amphigory, by Edward Gorey, was one of the most confusing and therefore intriguing works we have looked at all year. Due to the friendly and childish nature of the characters within his book, one would assume the stories the images describe to be more appropriate for a younger audience, but of course the stories contain mature content. The juxtaposition between Gorey’s child-friendly artistic style and his stories’ content is quite obvious and got me to wonder, what was Gorey’s view of his own artwork? I remembered a quote mentioned in class about how Gorey did not consider his work to be for children, so I looked the quote up and this is what I found:

“If you’re doing nonsense it has to be rather awful, because there’d be no point. I’m trying to think if there’s sunny nonsense. Sunny, funny nonsense for children — oh, how boring, boring, boring. As Schubert said, there is no happy music. And that’s true, there really isn’t. And there’s probably no happy nonsense, either.” Read more at: http://www.azquotes.com/quote/695116

This Gorey quote seems to perfectly summarize the way Gorey categorizes his work, however, I extremely disagree with Gorey in his evaluation. I think Gorey truly believed and wanted to convince people that his work was not for children, and that sad things did happen in his stories. Having said that, why would one read a book full of his stories if not to receive some sort of benefit or satisfaction? The characters are child-friendly, (actually remind me of characters in Roald Dahl books), why not make the characters in the stories more sinister in nature, to match the events that take place in the story? The nature of the cartoon drawings and the nonsensical nature of his stories make them entertaining and I would argue, have the ability to instill happiness in the viewer. While they may not be child-friendly stories, the stories are happy in the sense that they cause the audience to laugh or smile when reading them.

A Series of Gorey Events

While flipping through Amphigorey once again, I attempted to figure out why I found it so funny. What makes Amphigorey so darkly hilarious? I think a lot of it may have to do with his choice of language, his speech patterns, and their relationship with the genre/visual presentation.

Gorey’s writing has a quietly ironic, self-mocking air. The narrative world is set in the Victorian era, and when we think of this period of time we often imagine the self-involved, regimented, stifled, and posh upper class. When we think of writing from the 19th century, we think of ostentatious vocabulary, a stoic and ambiguous treatment of uncouth/inappropriate subjects, unnecessarily long sentences, and “proper” vocabulary. Every one of us could mock, when asked, old-timey speech patterns, and we often do so quite frequently.

Gorey utilizes these speech patterns and reinforces them with Victorian era images/characters. E.g.: “He must be mad to go on enduring the unexquisite agony of writing when it all turns out drivel.” The vocabulary he chooses helps to create this world steeped in the past: “oysters with trifle”? Who eats oysters with trifle these days? Additionally, people rarely “loiter in a distraught manner.” Seeing this type of language combined with childlike pictures and dark themes creates a contrast between presentation and connotation. Individuals in the Victorian era existed within a strict social code, a code that forbade impropriety, blatant sexuality, and discussion of “unpleasant” topics. They most likely would not have discussed “Prue, trampled flat in a brawl” in polite conversation, would have been astonished by the dark humor in The Fatal Lozenge. The triviality of Gorey’s details mimic the superficial, delicate conversation of the Victorian era, and conflicts with the decidedly serious, disturbing topics. The incongruity of these elements creates a ironic, amusing, uncomfortable jolt.

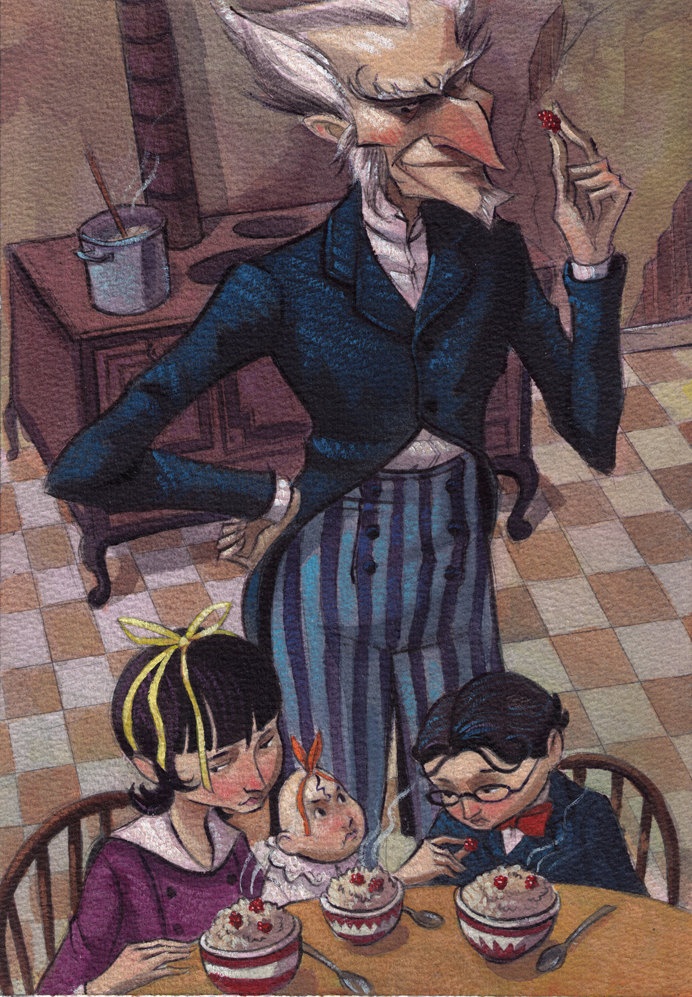

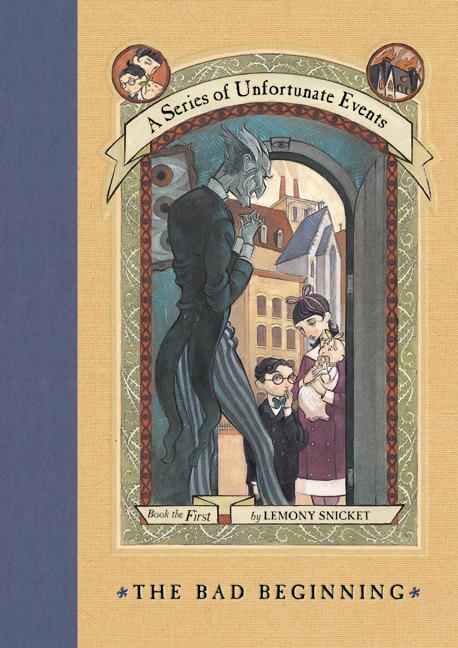

This is, by now, an established genre: mixing children’s books with macabre, dismal themes in a semi-fantastical Victorian setting. I was immediately reminded of A Series of Unfortunate Events. The books include illustrations, but they are mostly text. You can definitely see how “Lemony Snicket” (a pseudonym, just like Gorey often used) draws heavily from Gorey. Here are some pictures of the artwork (paratext!):

Snicket writes in a similar manner. Some quotes from the books in the series:

“If you are allergic to a thing, it is best not to put that thing in your mouth, particularly if the thing is cats.”

“Assumptions are dangerous things to make, and like all dangerous things to make – bombs, for instance, or strawberry shortcake – if you make even the tiniest mistake you can find yourself in terrible trouble.”

“It is one of the peculiar truths of life that people often say things that they know full well are ridiculous.”

Did you guys read these books, too? What do you think?